Every generation has a series of icons, symbols and cultural references that identify it, that constitute the shared common ground that consolidates it as a homogeneous group and that sets it apart from previous or future generations. Artists, writers, musicians, actors, politicians, activists form the core matter that over the course of a lifetime people pertaining to that generation will continuously turn back to, hailing them as unparalleled, unique—simply the best.

Comedians hold a curious status in this hierarchy of cultural significance: on the one hand, every generation has at least one universally recognizable comedian who can be singled out as a “genius”; on the other, “genius” suddenly becomes a relative terms as soon as it is ascribed to someone whose career revolvs around the seemingly banal task of popular entertainment. Just ask yourself who’s more of a genius and you’ll see what I mean: Charlie Chaplin or Bertrand Russell? Lucille Ball or Mark Rothko? Robin Williams or Steven Hawking?

Popular and entertainment are the two key operative words when it comes to Roberto Gómez Bolaños, aka “Chespirito,” a genius if there ever was one in his remarkable—unparalleled, unique—capacity to connect with the Latin American audience, from Mexico to Venezuela, from Chile to Miami. The most notorious comedian in television since the days of the also Mexican Mario Moreno, aka “Cantinflas,” Chespirito appealed to the people across a continent that spans 5,000 miles and a couple dozen different countries not by diluting the differences that arise from country to country but rather by identifying and highlighting in his sketches the emotional ties that in one way or another are common to humans in general.

In this regard, Chespirito’s sensibility sought to uncover through individual characters and circumstances a universal principle of what we call “human,” or better still “humane.” As Mexican as enchiladas or tequila, part of his undeniable success was to win over with his charm and his humor the favor of millions of people so deeply entrenched in their own nationalism that the mere sound of a vaguely different form of Spanish immediately triggers waves of derision and distrust. Mexican and Argentinean Spanish constitute the boundaries in Latin America of how laughably different accents (and by extension the people speaking them) can be. As the extreme poles of diversity, Mexican and Argentinean were equally reviled in Venezuela as I grew up. Chespirito transcended that antipathy, however, and achieved the not-insignificant accomplishment of having us—all the children of my generation—imitating his Mexican accent as we went over and over the sketches of his two trademark sitcoms, El Chapulín Colorado (1972-1979) and El Chavo del 8 (1973-1992).

The former was a satirical take on the American model of superheroes equipped with special powers that made them stand out above the rest, helped them overcome all obstacles and ultimately turned them into unassailable beings way beyond good and evil. Gómez Bolaños sought to create a hero who was anything but super, closer to the layman, and who consequently partook of the same problems and emotions that we all experience when faced with challenges. Thus, Chapulín Colorado (the hero’s name, which translates roughly as “crimson grasshopper”) is a clumsy, fearful and largely helpless hero with good intentions, a number of seemingly useless weapons and a healthy dose of guile. (Indeed, one of his trademark sentences is no contaban con mi astucia—“you didn’t think I’d be this smart.”)

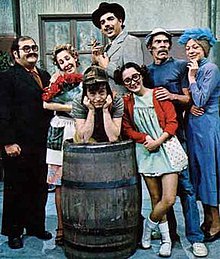

The preposterous setting of El Chapulín Colorado enabled Chespirito to use violence and explore some of the most negative aspects of human behavior within a safe context that warranted this sort of themes. But when he extrapolated many of these traits and placed them within the ordinary frame of reference of a housing complex in El Chavo del 8 (“the kid from number 8”) controversy followed. El Chavo focused on the lives of three children from a block of apartments and on their immediate surroundings. But the characters of this sitcom are markedly shaped by their negative traits: Chavo is a destitute and slow-witted orphan who lives in a barrel; Chilindrina is a manipulative girl whose single father is an alcoholic and abusive former boxer; Quico is pretentious and his single mother a disgraced snob. Despite their differences the children develop a strong affective bond, a love-hate relationship of sorts in which each is always trying to upend the other by any means possible, legitimate or not.

Critics pointed at El Chavo as a negative portrayal of the basest strata of society, denigrating in its depiction of poverty, simplistic in its treatment of social problems, approving of the use of violence and exploitative of the misery of others. Indeed, so polarized was opinion about the show in Venezuela that I knew several children who were not allowed to watch it on TV (in the same way that some children were not allowed to watch The Simpsons or own Garbage Pail Kids trading cards because they were deemed to be excessively vulgar, violent, immoral). Be that as it may, El Chavo, like The Simpsons, prevailed, becoming an emblematic sitcom that shaped the tastes and childhood of hundreds of millions of people through the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s.

Roberto Gómez Bolaños died at the age of 85 last Friday, November 28th 2014. His passing has revived many of the arguments surrounding his creations and his personal relationship with a number of the members of the cast of El Chavo, el Chapulín Colorado and his own personal show, Chespirito, which featured sketches of these and other productions. His fallout in 1978 with Carlos Villagrán, who played the role of Quico, was widely publicized and ultimately led to the end of El Chapulín Colorado and of the first run of El Chavo, once Ramón Valdés (Chilindrina’s father, Don Ramón) also announced his retirement due to personal differences the following year.

El Chavo would return as part of Chespirito in 1981 and continue to feature in the show until 1992. By then, Gómez Bolaños was over 60 years old, and still engaging in his role as an 8-year-old child. Because in many ways the children of El Chavo were not really meant to be children—just like Chapulín Colorado was not meant to be a superhero. In many ways the creases and fissures that many detractors of El Chavo point at as shortcomings in Gómez Bolaños’ production are precisely the nuances that make his shows so popular—simple, honest, unapologetic depictions of our flawed selves. El Chavo was not about children misbehaving: it was about adults acting the role of children who follow the example given to them by adults and consequently misbehave. The difference might be subtle, but it’s also crucial.

Inevitably, comparisons will arise. Despite the fear, threat or expectation of globalization turning our world into a single, uniform and identical unit there are still some things that simply don’t travel well: Americans in their 20s or their 60s won’t understand the significance of Chespirito in the same way—perhaps—that Venezuelans in their 30s don’t get Gilligan’s Island.

For Venezuelans, for Latin Americans in their 30s, this has been a delicate year: earlier in 2014 Gustavo Cerati, perhaps the most influential musician in the history of Spanish rock, passed away. Now it is Chespirito’s turn to wave the long goodbye. Neither departure has been unexpected—Gómez Bolaños was 85, and Cerati had been in a coma for four years—but both have brought with them vivid and dear memories of times past. Not necessarily better times, or even highly remarkable times—just key times in the development of an entire generation’s identity. Thus, while cultural theorists in some corner of this partially globalized world discuss the influence of El Chavo compared to, say, Mork & Mindy, in homes across Latin America millions of children (or perhaps rather their parents) will still be laughing (and crying) at the sheer humaneness of Roberto Gómez Bolaños’ creations. Thanked be the heavens for reruns!

Published in the WEEKender supplement of Sint Maarten’s The Daily Herald on Saturday December 6th 2014.