When Saul Bellow was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in 1976, he’d already been heralded as the savior and re-inventor of the novel for over two decades. 2015 was doubly significant for Bellow enthusiasts as it marked both the hundredth anniversary of his birth and the tenth anniversary of his death. Consequently, much has been written this year about Bellow, an otherwise strangely forgotten figure of modern literature, or perhaps simply one that had been temporarily shelved, unceremoniously set aside but not quite discarded, lying in wait for a new turn in the tide of fashion that might bring him back into the limelight.

The son of Russian Jewish immigrants, Bellow was born just over a year after his parents arrived, illegally, in Canada. However, it is as a Chicagoan that he grew to fame, painting a detailed, entertaining and absolutely vast picture of the essence of the city in his lengthy novels. And yet, the move that would determine Saul Bellow’s prolific career almost didn’t take place, because before being smuggled from Canada to Chicago as a nine-year-old he had a close encounter with death through a respiratory illness that nearly claimed his life a year earlier. Bellow survived, though, and adapted to life in the city of hoodlums and mobsters in the days immediately before and after the Great Depression.

Bellow’s first two novels, The Dangling Man (1944) and The Victim (1947), earned him a reputation as a “serious” writer, even if he was himself later critical of them. His true breakthrough, however, came with the publication in 1953 of The Adventures of Augie March. Widely considered his masterpiece, this novel traces the story of a sympathetic ragamuffin from Chicago, Augie March, from his childhood as a young member of a family of Jewish immigrants, through his exploits in Mexico and New York, to his experiences in France during the war. Structured in the form of a picaresque novel, Augie March is not so much a response to but a reinterpretation of the likes of the Spanish Life of Lazarillo de Tormes (1554) or Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759).

Bellow would have been aware of this tradition, and yet, in supreme ironic fashion, he boastfully stakes a claim to originality in the opening sentence of the book: “I have taught myself, free-style, and will make the record in my own way: first to knock, first admitted.” There is no contradiction in this assertion either, because what Bellow does is deliberately (and consciously) stress the tension between the structure of Augie March—the most traditional format, the original template, as it were, of the novel as a genre—and the contribution he is presently bringing to the table: the formulation of a new, freer form of expression, a use of language that is in tune with the New World, fit for the new era, with no strings attached to the past. In other words, the language of a man such as Augie himself, self-taught and opportunistic.

Bellow would have been aware of this tradition, and yet, in supreme ironic fashion, he boastfully stakes a claim to originality in the opening sentence of the book: “I have taught myself, free-style, and will make the record in my own way: first to knock, first admitted.” There is no contradiction in this assertion either, because what Bellow does is deliberately (and consciously) stress the tension between the structure of Augie March—the most traditional format, the original template, as it were, of the novel as a genre—and the contribution he is presently bringing to the table: the formulation of a new, freer form of expression, a use of language that is in tune with the New World, fit for the new era, with no strings attached to the past. In other words, the language of a man such as Augie himself, self-taught and opportunistic.

This is the single most significant aspect not only of The Adventures of Augie March but of Bellow’s literary output altogether. In some sense, Bellow’s fiction becomes—let’s not say a prisoner but—a justification for his authorial voice. One of the great clichés of literary fiction is that authors often dismiss plot and structure as little more than decorations to embellish their perfectly formed characters. In Bellow the stereotype finds a primary exponent, as he rambles impudently, flaunting his peculiar, infectious, often hilarious style well beyond the boundaries of cohesion or even coherence. The thing is, though, that when it works, it works so well that it actually doesn’t even matter where the narrative is taking you—the read is so exhilarating you sign up just for the ride.

The ride of Seize the Day, however, the 1956 novella that followed the phenomenal success of The Adventures of Augie March, is the polar opposite to its predecessor’s. Succinct, with a streamlined structure and a simple plot, Seize the Day traces twenty-four hours in the life of one-time charmer Tommy Wilhelm, whose fall from grace is less tragic than mundane. Faced with the prospect of bankruptcy, Wilhelm entrusts his last savings to the cryptic Dr. Tamkin to invest in the stock market. Dr. Tamkin is a suave if rather bumptious charlatan, and Wilhelm’s father, Dr. Adler, a man of substance, principles and above all concrete facts, cannot stand the sight of him. But Dr. Adler is an old man in his last legs, and this is an age of intangibles ahead of commodities, an age in which trust and instinct can make you more in the stock market than the actual goods sold.

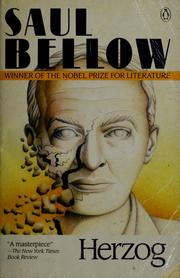

Like much of Bellow’s fiction, Seize the Day is concerned with the condition of modern man, with the place of everyday banality in the great scheme of things, with the compatibility of a practical life in which women (and lawyers) conspire to strip men of all their money versus the great ideas of old which until now had always been conceived of as “universal.” To some extent this too is the concern of Bellow’s most successful novel, Herzog (1961), a semi-autobiographical rendition of Bellow/Herzog’s descent into the clutches of insanity after he discovers his much younger wife has been having an affair with his best friend for years.

Like much of Bellow’s fiction, Seize the Day is concerned with the condition of modern man, with the place of everyday banality in the great scheme of things, with the compatibility of a practical life in which women (and lawyers) conspire to strip men of all their money versus the great ideas of old which until now had always been conceived of as “universal.” To some extent this too is the concern of Bellow’s most successful novel, Herzog (1961), a semi-autobiographical rendition of Bellow/Herzog’s descent into the clutches of insanity after he discovers his much younger wife has been having an affair with his best friend for years.

Herzog’s MO once he is in full crisis mode is to sit and write (like Bellow) undelivered (and mostly unfinished) letters to all sorts of prominent people in his life, from an old professor to dead philosophers and even President Eisenhower. These letters differ drastically in tone from the main narrative voice, show great erudition in a vast number of fields, and in a way allow Bellow to infiltrate his story with an alternative discourse. The digressions add effective and immediate comedic value to the whole, to be sure, but they also provide a sobering perspective on the validity of academic or proto-academic language: by inserting perfectly legitimate samples of human knowledge and rendering them useless in the context of the novel, Bellow brings down a notch the tremendous repute enjoyed by science, religion or even economy in our everyday postmodern life.

The climax of Bellow’s extraordinary literary career came when he published Humboldt’s Gift in 1975. Having previously won the National Book Award three times for Augie March, Herzog and Mr. Sammler’s Planet (1970), he was finally awarded the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in April 1976. A few months later the Swedish Academy came knocking with Nobel Prize too. Bellow, by now, was King Bellow.

As is often the case, though, his production after 1976 failed to reach the critical acclaim it had garnered over the previous two decades. To Caribbean readers, however, his last ever novel, Ravelstein (2000), will be of particular interest.

Like his move to Chicago at the age of nine, Ravelstein almost never happened, as Bellow became critically ill in December 1994 following a holiday trip to St. Martin which ended disastrously when he ate poisoned reef fish. He was flown back to Boston almost immediately by his fifth wife Jane, and only barely escaped death from ciguatera poisoning which for three weeks left him completely incapacitated, hallucinating and unable even to write his name on a piece of paper. Ultimately, however, Lady Luck smiled on Bellow again at the age of eighty, as she had at the age of eight, and bad fish as well as St. Martin made it prominently into the plot of Ravelstein.

Bellow would live another ten years after the bout of ciguatera but his reputation would slowly go into hibernation. To this day he is praised enormously, above all by writers, when his name comes up in conversation—it’s just that it comes up less and less often. The reason for it might be that we have, by now, assimilated much of what is great in his work. Bellow’s gift to literature was to liberate the prose of the post-war generation from the convention that, to a large extent, continued to exert its tyranny over modern literature. More than half a century later, though, the shadow of those ties has faded, and the rebellious vein in his writing and that of others in his generation—such as J. D. Salinger, for instance—consequently seems less momentous. Some people might argue that Bellow’s Augie March, that Salinger’s Holden Caulfield, are no longer relevant to our modernity. If that is so, however, the loss is entirely ours.

Published by The Weekender supplement of Sint Maarten’s The Daily Herald on Saturday January 7 2016.